I'm reminded by the newest argument of a passage in The New Jim Crow:

I'm also reminded of an editorial written by Michelle Alexander, the author of The New Jim Crow:

And I'm reminded of Ta-Nehisi Coates' post on Patrick Sharkey's "Neighborhoods and The Mobility Gap" study is useful:

Just to illustrate the gap, Sharkey's research shows that black families making $100,000 typically live in the kinds of neighborhoods inhabited by white families making $30,000. In other words, black upper-middle class families often do not live in what would be considered upper-middle class neighborhoods.

That said, there are still advantages inherent to being in the middle class apart from the financial. In Annette Lareau's Unequal Childhoods: Race, Class, and Family Life, she goes into considerable depth explaining how family dynamics are influenced by class differences by doing an ethnographic study with a large cross-section of poor, working-class, and middle-class families, to see how the dynamics work out in practice. For instance, she demonstrates how middle class parents differed from working class and poor parents in their fundamental conception of what their responsibilities as parents included. Middle class parents worked to engage their kids in "concerted cultivation." These parents see themselves as developing their children's talents, by engaging them in a way array of organized activities, from which those same kids develop a sense of entitlement, and learn to question adults and address them as relative equals. Children in middle class homes also experienced more talking, which led to "greater verbal agility, larger vocabularies, more comfort with authority figures, and more familiarity with abstract concepts." They also "developed skill differences in interacting with authority figures in institutions and at home."

And I know that we're used to treating "entitlement" as a bad thing, but it is advantageous today:

The working class and poor parents, by contrast, attempt to facilitate the "accomplishment of natural growth." This does have its advantages - the children of these families rarely complain of boredom, the field researchers never saw the sort of common expressions of hatred that they saw in middle class homes, the kids tended to be more self-directed in terms of finding their own entertainment, they were more comfortable with hanging out with groups with wide disparities in age range, and they were better at handling their disputes without the help of an adult. But these kids also developed disadvantages; while the children of the middle-class parents were learning entitlement the cultural logic of these parents was out of step with that of the primary institution - school - that their children interacted with. These children developed a sense of "distance, distrust, and constraint in their institutional experiences."

One of the best examples of this difference in institutional experiences is a doctor's visit. In the case of the middle-class child, his parent coaches him on the idea of asking questions, encourages him to be thinking about questions before he gets there, and this child is encouraged in his attempt to ask questions by the doctor taking him seriously. By contrast, the child of the working-class parent did not evince the same sense of entitlement to ask questions of the doctor, which meant that in this instance, there was a disparity in the quality and amount of information divulged. This is one way that middle-class parents are able to transmit advantages for their children - simply by knowing how to be assertive and how to interact with institutional authority figures. For instance, when one middle-class mother's daughter misses the cut-off for the gifted-and-talented program by two points (128 out of 130 required) on the IQ score, rather than simply accepting the judgment of the institution, she used advice from school educators and tips from friends in other districts, learned the guidelines for appealing a decision, and had her daughters tested privately (at $200 a child) and was able to get her children admitted into the program. The children of middle-class parents learn to approach relationships with institutional authority figures as negotiable, and ones in which they can assert their desires and their needs and expect to be taken seriously. By contrast, over and over again the parents of working-class or poor parents learn a sense of restraint and of almost learned helplessness in their interactions with authority figures.

Even if race weren't an issue in and of itself, the problem of class would present an enormous barrier to achieving racial equality because of the deep-seated disparities.

"... One recent study indicates that the elimination of race-based admissions policies would lead to a 63 percent decline in black matriculants at all law schools and a 90 percent decline at elite law schools. Sociologist Stephen Steinberg describes the bleak reality this way: "Insofar as this black middle class is an artifact of affirmative action policy, it cannot be said to be the result of autonomous workings of market forces. In other words, the black middle class does not reflect the lowering of racist barriers in occupations so much as the opposite: racism is so entrenched that without government intervention there would be little 'progress' to boast about."

In view of all this, we must ask, to what extent has affirmative action helped us remain blind to, and in denial about, the existence of a racial underclass?"

In view of all this, we must ask, to what extent has affirmative action helped us remain blind to, and in denial about, the existence of a racial underclass?"

I'm also reminded of an editorial written by Michelle Alexander, the author of The New Jim Crow:

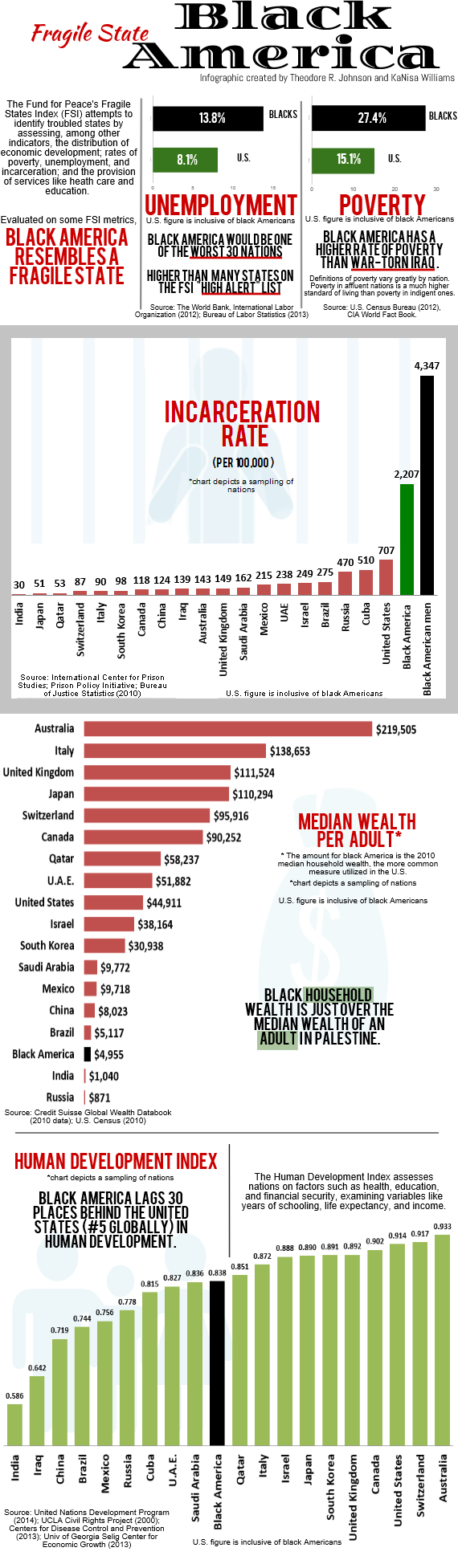

Recent data shows, though, that much of black progress is a myth. In many respects, African-Americans are doing no better than they were when Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated and uprisings swept inner cities across America. Nearly a quarter of African-Americans live below the poverty line today, approximately the same percentage as in 1968. The black child poverty rate is actually higher now than it was then. Unemployment rates in black communities rival those in Third World countries. And that's with affirmative action!

When we pull back the curtain and take a look at what our "colorblind" society creates without affirmative action, we see a familiar social, political, and economic structure--the structure of racial caste. The entrance into this new caste system can be found at the prison gate.

When we pull back the curtain and take a look at what our "colorblind" society creates without affirmative action, we see a familiar social, political, and economic structure--the structure of racial caste. The entrance into this new caste system can be found at the prison gate.

And I'm reminded of Ta-Nehisi Coates' post on Patrick Sharkey's "Neighborhoods and The Mobility Gap" study is useful:

Among children born from 1955 through 1970, only 4 percent of whites were raised in neighborhoods with at least 20 percent poverty, compared to 62 percent of blacks. Three out of four white children were raised in neighborhoods with less than 10 percent poverty, compared to just 9 percent of blacks. Even more astonishingly, essentially no white children were raised in neighborhoods with at least 30 percent poverty, but three in ten blacks were.

And more shockingly still, almost half (49 percent) of black children with family income in the top three quintiles lived in neighborhoods with at least 20 percent poverty, compared to only one percent of white children in those quintiles. These figures reveal that black children born from the mid 1950s to 1970 were surrounded by poverty to a degree that was virtually nonexistent for whites.

This degree of racial inequality is not a remnant of the past. Two out of three black children born from 1985 through 2000 have been raised in neighborhoods with at least 20 percent poverty, compared to just 6 percent of whites. Only one out of ten blacks in the current generation has been raised in a neighborhood with less than 10 percent poverty, compared to six out of ten whites. Even today, thirty percent of black children experience a level of neighborhood poverty -- a rate of 30 percent or more -- unknown among white children.

And more shockingly still, almost half (49 percent) of black children with family income in the top three quintiles lived in neighborhoods with at least 20 percent poverty, compared to only one percent of white children in those quintiles. These figures reveal that black children born from the mid 1950s to 1970 were surrounded by poverty to a degree that was virtually nonexistent for whites.

This degree of racial inequality is not a remnant of the past. Two out of three black children born from 1985 through 2000 have been raised in neighborhoods with at least 20 percent poverty, compared to just 6 percent of whites. Only one out of ten blacks in the current generation has been raised in a neighborhood with less than 10 percent poverty, compared to six out of ten whites. Even today, thirty percent of black children experience a level of neighborhood poverty -- a rate of 30 percent or more -- unknown among white children.

Previous research has used a measure of neighborhood disadvantage that incorporates not only poverty rates, but unemployment rates, rates of welfare receipt and families headed by a single mother, levels of racial segregation, and the age distribution in the neighborhood to capture the multiple dimensions of disadvantage that may characterize a neighborhood.

Figure 2 shows that using this more comprehensive measure broken down into categories representing low, medium, and high disadvantage, 84 percent of black children born from 1955 through 1970 were raised in "high" disadvantage neighborhoods, compared to just 5 percent of whites. Only 2 percent of blacks were raised in "low" disadvantage neighborhoods, compared to 45 percent of whites. The figures for contemporary children are similar.

By this broader measure, blacks and whites inhabit such different neighborhoods that it is not possible to compare the economic outcomes of black and white children who grow up in similarly disadvantaged neighborhoods. However, there is enough overlap in the childhood neighborhood poverty rates of blacks and whites to consider the effect of concentrated poverty on economic mobility.

Figure 2 shows that using this more comprehensive measure broken down into categories representing low, medium, and high disadvantage, 84 percent of black children born from 1955 through 1970 were raised in "high" disadvantage neighborhoods, compared to just 5 percent of whites. Only 2 percent of blacks were raised in "low" disadvantage neighborhoods, compared to 45 percent of whites. The figures for contemporary children are similar.

By this broader measure, blacks and whites inhabit such different neighborhoods that it is not possible to compare the economic outcomes of black and white children who grow up in similarly disadvantaged neighborhoods. However, there is enough overlap in the childhood neighborhood poverty rates of blacks and whites to consider the effect of concentrated poverty on economic mobility.

The main conclusion from these results is that neighborhood poverty appears to be an important part of the reason why blacks experience more downward relative economic mobility than whites, a finding that is consistent with the idea that the social environments surrounding African Americans may make it difficult for families to preserve their advantaged position in the income distribution and to transmit these advantages to their children.

When white families advance in the income distribution they are able to translate this economic advantage into spatial advantage in ways that African Americans are not, by buying into communities that provide quality schools and healthy environments for children. These results suggest that one consequence of this pattern is that middle-class status is particularly precarious for blacks, and downward mobility is more common as a result.

When white families advance in the income distribution they are able to translate this economic advantage into spatial advantage in ways that African Americans are not, by buying into communities that provide quality schools and healthy environments for children. These results suggest that one consequence of this pattern is that middle-class status is particularly precarious for blacks, and downward mobility is more common as a result.

Just to illustrate the gap, Sharkey's research shows that black families making $100,000 typically live in the kinds of neighborhoods inhabited by white families making $30,000. In other words, black upper-middle class families often do not live in what would be considered upper-middle class neighborhoods.

That said, there are still advantages inherent to being in the middle class apart from the financial. In Annette Lareau's Unequal Childhoods: Race, Class, and Family Life, she goes into considerable depth explaining how family dynamics are influenced by class differences by doing an ethnographic study with a large cross-section of poor, working-class, and middle-class families, to see how the dynamics work out in practice. For instance, she demonstrates how middle class parents differed from working class and poor parents in their fundamental conception of what their responsibilities as parents included. Middle class parents worked to engage their kids in "concerted cultivation." These parents see themselves as developing their children's talents, by engaging them in a way array of organized activities, from which those same kids develop a sense of entitlement, and learn to question adults and address them as relative equals. Children in middle class homes also experienced more talking, which led to "greater verbal agility, larger vocabularies, more comfort with authority figures, and more familiarity with abstract concepts." They also "developed skill differences in interacting with authority figures in institutions and at home."

And I know that we're used to treating "entitlement" as a bad thing, but it is advantageous today:

This kind of training developed in Alexander and other middle-class children a sense of entitlement. They felt they had the right to weigh in with an opinion, to make special requests, to pass judgment on others, and to offer advice to adults. They expected to receive attention and to be taken very seriously. It is important to note that these advantages and entitlements are historically specific. In colonial America, for example, children's actions were highly restricted; thus, the strategies associated with concerted cultivation would have conferred no social class advantage. They are highly effective strategies in the United States today precisely because our society places a premium on assertive, individualized actions executed by persons who command skills in reasoning and negotiation.

The working class and poor parents, by contrast, attempt to facilitate the "accomplishment of natural growth." This does have its advantages - the children of these families rarely complain of boredom, the field researchers never saw the sort of common expressions of hatred that they saw in middle class homes, the kids tended to be more self-directed in terms of finding their own entertainment, they were more comfortable with hanging out with groups with wide disparities in age range, and they were better at handling their disputes without the help of an adult. But these kids also developed disadvantages; while the children of the middle-class parents were learning entitlement the cultural logic of these parents was out of step with that of the primary institution - school - that their children interacted with. These children developed a sense of "distance, distrust, and constraint in their institutional experiences."

One of the best examples of this difference in institutional experiences is a doctor's visit. In the case of the middle-class child, his parent coaches him on the idea of asking questions, encourages him to be thinking about questions before he gets there, and this child is encouraged in his attempt to ask questions by the doctor taking him seriously. By contrast, the child of the working-class parent did not evince the same sense of entitlement to ask questions of the doctor, which meant that in this instance, there was a disparity in the quality and amount of information divulged. This is one way that middle-class parents are able to transmit advantages for their children - simply by knowing how to be assertive and how to interact with institutional authority figures. For instance, when one middle-class mother's daughter misses the cut-off for the gifted-and-talented program by two points (128 out of 130 required) on the IQ score, rather than simply accepting the judgment of the institution, she used advice from school educators and tips from friends in other districts, learned the guidelines for appealing a decision, and had her daughters tested privately (at $200 a child) and was able to get her children admitted into the program. The children of middle-class parents learn to approach relationships with institutional authority figures as negotiable, and ones in which they can assert their desires and their needs and expect to be taken seriously. By contrast, over and over again the parents of working-class or poor parents learn a sense of restraint and of almost learned helplessness in their interactions with authority figures.

Even if race weren't an issue in and of itself, the problem of class would present an enormous barrier to achieving racial equality because of the deep-seated disparities.