-

Hey, guest user. Hope you're enjoying NeoGAF! Have you considered registering for an account? Come join us and add your take to the daily discourse.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

31 Days of Horror 4 |OT| The October Movie Marathon

- Thread starter ThirstyFly

- Start date

Final sanity check: Yeah, this was a great, great year. Despite some bumps in the road, some of them literal in the case of the short road trip I took to Myrtle Beach the weekend before Halloween, this was a lot of quality stuff, and I even found some new unimpeachable favorites for me to cherish. I much prefer sticking to a smaller selection of films, too, so that's going to be the standard going forward, although I feel like the five full weeks is also important for me.

So, I don't know the list yet of course, but next year will be the seventh year of doing a marathon, and what better way to commemorate it than doing the marathon comprised entirely of 70s horror? There was quite a bit of that decade in this year's run, and there's a hell of a lot more films to uncover from that weird, wild decade of filmmaking. I can't wait to see what's in store for me!

Unquestionably awesome films: Rituals, Just Before Dawn, Re-animator, Altered States, Dead Ringers, The Descent, Ms. 45, The Loved Ones, Picnic at Hanging Rock, and Pieces (well, that might be questionable!)

Biggest surprises: Ravenous, The Sender, Pin, Amer, Rogue, Night of the Creeps, Brain Damage

Biggest disappointments: Sleepaway Camp, May, We Need to Talk About Kevin, Torso

Seriously, don't watch this awful piece of shit: Anatomy

So, I don't know the list yet of course, but next year will be the seventh year of doing a marathon, and what better way to commemorate it than doing the marathon comprised entirely of 70s horror? There was quite a bit of that decade in this year's run, and there's a hell of a lot more films to uncover from that weird, wild decade of filmmaking. I can't wait to see what's in store for me!

Unquestionably awesome films: Rituals, Just Before Dawn, Re-animator, Altered States, Dead Ringers, The Descent, Ms. 45, The Loved Ones, Picnic at Hanging Rock, and Pieces (well, that might be questionable!)

Biggest surprises: Ravenous, The Sender, Pin, Amer, Rogue, Night of the Creeps, Brain Damage

Biggest disappointments: Sleepaway Camp, May, We Need to Talk About Kevin, Torso

Seriously, don't watch this awful piece of shit: Anatomy

kurisu1974

Banned

Still have to post my endgame!

28. Silent House (Chris Kentis and Laura Lau, 2011)

Another completely useless Hollywood remake, I wasn't that big a fan of the Uruguayan original, and while Elisabeth Olsen is nice to look at, this was just completely interesting especially when you have seen it before.

29. Las Brujas de Zugarramurdi (Alex de la Iglesia, 2013)

This was great fun, especially the first part of the movie, and there's some Almodovar vibes there, even if De la Iglesia always manages to contruct his own unique universes. The end boss of this movie you'll not easily forget. Also know under the retarded title Witching & Bitching.

30. Dracula (John Badham, 1979)

I enjoyed this rather convenient take on the well know subject very much, it was funny and witty, with great sets and actors. Frank Lagella did a great Dracula. Recommended.

31. American Mary (The Soska Sisters, 2012)

I bought into this thread's hype for this movie, I kinda wish I hadn't. At best this is a nice curiosity because of those weird people that try to act in it, but I was moslty bored by the TV style aesthetics and amateur hour acting, and lack of any tension or real story.

So that's it! Didn't watch a bunch of movies that I wanted to include, and watched a bunch of movies that I wish I didn't

28. Silent House (Chris Kentis and Laura Lau, 2011)

Another completely useless Hollywood remake, I wasn't that big a fan of the Uruguayan original, and while Elisabeth Olsen is nice to look at, this was just completely interesting especially when you have seen it before.

29. Las Brujas de Zugarramurdi (Alex de la Iglesia, 2013)

This was great fun, especially the first part of the movie, and there's some Almodovar vibes there, even if De la Iglesia always manages to contruct his own unique universes. The end boss of this movie you'll not easily forget. Also know under the retarded title Witching & Bitching.

30. Dracula (John Badham, 1979)

I enjoyed this rather convenient take on the well know subject very much, it was funny and witty, with great sets and actors. Frank Lagella did a great Dracula. Recommended.

31. American Mary (The Soska Sisters, 2012)

I bought into this thread's hype for this movie, I kinda wish I hadn't. At best this is a nice curiosity because of those weird people that try to act in it, but I was moslty bored by the TV style aesthetics and amateur hour acting, and lack of any tension or real story.

So that's it! Didn't watch a bunch of movies that I wanted to include, and watched a bunch of movies that I wish I didn't

avengers23

Banned

1. October 1 - Sinister (DVR) - Worth watching

2. October 2 - Shadow of the Vampire (DVR) - Worth watching

3. October 3 - The Exorcism of Emily Rose (DVR) - Worth Watching

4. October 4 - Would You Rather (DVR) - Worth watching

5. October 5 - Excision (DVR) - Worth watching

6. October 6 - Evil Dead (2013) (DVR) - Meh

7. October 7 - Angel Heart (DVR) - Worth watching

8. October 8 - The Lords of Salem (DVR) - Meh

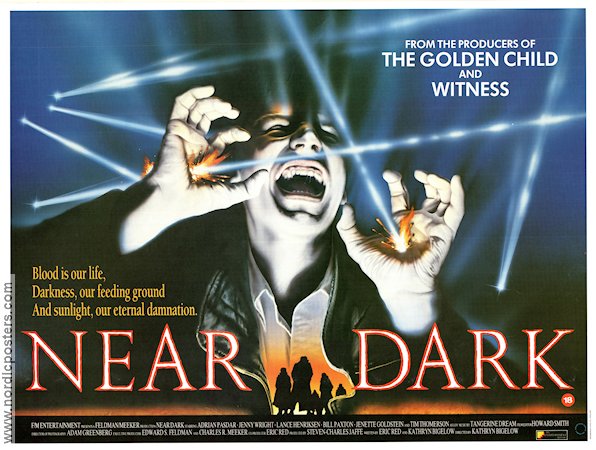

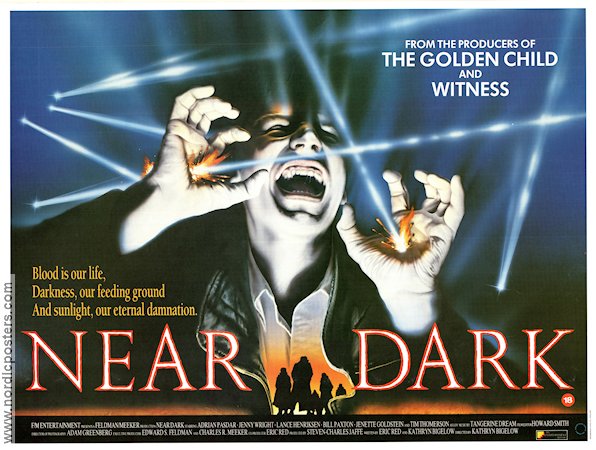

9. Near Dark *(1987) (DVR)

At this point, Near Dark has reached nearly legendary status among my circle of friends, so I started the film with great expectations and some trepidation after Angel Heart failed to meet expectations. Its mix of the sensibilities of the western, the biker movie, and the vampire movie is enticing, but what surprised me was how tender the film was. Mae probably loves Caleb more when he admits that he can’t be the kind of killer who can stand in Jesse’s clan of vampires alongside violent creatures like Severen or Homer. Mae turns Caleb because she’s lonely and wants someone with whom she could spend eternity; Jesse and Diamondback look back on his attack that turned her wistfully. It made me wonder what happens after the end of the film, when Mae has been turned back to human and can live with Caleb not to the end of time, but at least for a little while. We can’t be sure she’s from contemporary times, but it doesn’t look like she has trouble living in the modern world. But people grow and change; would Mae feel like she owes Caleb for turning her back to human? Would she resent Caleb? Would Caleb resent Mae for resenting him? Would the freedom from the existential loneliness of a vampire's existence be enough for Mae?

We never see the vampires bare their fangs, which is an interesting choice that recalls George Romero’s Martin. This choice positions them more like an outlaw biker gang or the Manson Family, a group of killers united by a charismatic leader. They’re forced to be scavengers by what they are; they could choose to withdraw from the world and emerge only when they need to feed, but since they’re uninhibited by society’s rules, they may as well enjoy what they have.

There’s probably something significant to the fact that Caleb and his sister, Sarah, are cared for by their single father, but I can’t figure out what it is. In westerns, the civilized woman, usually a mother, represents civilization that inspires the gunfighters. In this case, does the absence of a mother make Caleb and his sister vulnerable to Jesse and his gang of outsiders?

Near Dark, like its 1987 compatriot Angel Heart, was a surprisingly influential film. While the rule about vampires' fear of sunlight is critical to the vampire's story, Near Dark was the first to show in such graphic terms how sunlight affects vampires. Writer and director Kathryn Bigelow and writer Eric Red inject the specificity of a vampire's existence to standard action sequences like car chases (every window must be covered) and shoot-outs (the bullets can be laughed off, but the pinpricks of sunlight created by the bullet holes are dangerous). And you can draw a fairly straight line from Mae, her conscience, and her desire to be human to Angel of Buffy the Vampire Slayer and from Severen to Spike in Buffy, among other cool vampires. However, the Bigelow's style is derivative of James Cameron's The Terminator, which left a long shadow over action films of the 1980s, and the film looks very similar to Eric Red's The Hitcher.

The fairly happy ending that saw the use of barnyard blood transfusions to transform Caleb and Mae back human seemed weak, particularly when Adrian Pasdar's Caleb is the least interesting character of the film. Every moment we spend with Caleb and Mae is a moment we don't spend with Jesse, Diamondback, Severen, and Homer.

Finally, it bugged me that the soundtrack with its clangs and clashes sounded so familiar until I realized that Christopher Franke, who provided the soundtrack to Babylon 5, was a member of Tangerine Dream, which provided the soundtrack to Near Dark. There are moments when the soundtrack sounds exactly like the theme for Babylon 5’s third season opening credits.

10. Warm Bodies (2013) (DVR)

This movie was better than it had any right to be. Sure, it’s clichéd as hell; it even features a character named Julie and a balcony scene straight from Romeo and Juliet. Sure, John Malkovich is slumming it in this movie for the paycheck so obviously that it’s borderline offensive. And sure, the movie loses pretty much all momentum about halfway through the film, when the focus shifts on the unlikely romance between a zombie boy named “R,” played by Nicholas Hoult, and the aforementioned Julie, played by Teresa Palmer. But the opening act, particularly where R’s wry mental monologue takes us through his world, actually works very well.

The romance at the center of the film is problematic, to say the least. At best, it’s a story about a girl who falls in love with her undead kidnapper who might only be in love with her because he ate her boyfriend’s brain and inherited his memories and emotional connections. At worst, it brings up memories of abusive relationships like the one at the center of The CW’s Beauty and the Beast. Putting this aside, it’s still a fairly twee (they bond over vinyl records, which R prefers because the sound is more vibrant, or, you know, alive, and a carefully displayed bottle of Corona), low-key, passive teen romance. Whatever danger that existed at the heart of the romance between what is ostensibly a predator and its prey is neutered, and the external danger that comes from Julie’s father is thrown out because he basically steps back and accepts this weird, new relationship.

The world is a mishmash of concepts. On the one hand, we are invited to accept that the world is truly screwed. Beautiful teenagers and young adults have to be sent into the dangerous world beyond the city’s walls to scavenge for supplies. One of the manufacturing centers that the city relies on is overrun by zombies. The city, as far as it knows, is completely alone. On the other hand, detecting the zombie infection is as simple as a retinal scan, and those teenagers and young adults are treated to a video message by Malkovich’s character before they are sent outside.

Assimilation comes easy in this world. A bit of make-up, and a zombie can pass for a human. A bit of lurching and groaning, and a human can pass for a zombie. And with enough time, zombies can become humans again, and apparently people are more than happy to be romanced by former zombies, as the last scene featuring Rob Cordrry’s “M” shows. It’s the most optimistic view of human nature and its prejudices I've seen in a zombie film.

11. Byzantium (2013) (DVR)

The combination of Neil Jordan and Saorise Ronan sold me, and the lush and moody cinematography kept me. Jordan revisits the vampire’s ennui without reminding the viewer too much of his Interview With the Vampire, though both films feature vampires recounting their lives to nearby mortals. There are scenes where Ronan’s Eleanor, a vampire, is dressed in a red hood, that invite the viewers to remember the red hooded killer from Don’t Look Now and Little Red (and the Wolf). Unfortunately, what we see in flashbacks don’t reward the viewer for the time invested, and the time in the present seems very still.

The film tries to draw parallels about predatory violence between a man forcing a girl into a life of prostitution with a man turning a girl into a vampire, but we don’t spend enough time in the flashbacks to make those parallels stick. Jordan prefers the reserved tone, but the film feels practically lifeless for how much it holds back, especially in comparison to films like Let the Right One In or even Let Me In. Even the visceral moments of Byzantium feel like they were included only to wake the audience up every now and then; they feel intrusive.

12. Rare Exports: A Christmas Tale (2010) (DVR)

Any sufficiently clever child will remind you that “Santa” is an anagram for “Satan.” It’s not difficult to find the trace sinister elements that remain after years of pop culture telling us how about cuddly and comfortable we should feel about a character who uses slave labor in his workshop, who utilizes a global privacy-destroying surveillance system to monitor our behavior, who judges us by his code of morality, who breaks into our homes annually, and whose very code of behavior implies a threat if we violate his rules. The line between Santa Claus and the Punisher is fairly thin. Children can sense the Santa menace, which is why they hate to take photos with Santa cosplayers.

Santa Claus is a fairly popular character to deconstruct; Futurama’s Robot Santa Claus makes his implicit threat to everyone’s safety literal, while American Dad’s Santa Claus is a violent, vengeful baron of the North Pole. But even the more innocent deconstructions are vicious. Tim Allen’s character in The Santa Clause becomes Santa Claus against his will because he was infected by the Santa Clause, transmitting through donning the traditional Santa Claus outfit. His character undergoes a traumatic physical transformation, and his elfish paramilitary task force, the Effective Liberating Flight Squad, is deployed to break Santa Claus out of prison when he is captured by American authorities. In the end, Tim Allen’s character must abandon his family and his old life because he has been fully subsumed into the Santa Claus identity. No one would think that a Disney movie about Santa Claus would have so much body and psychological horror inside, but that’s the menace that Santa Claus presents leaking through the Disneyfied exterior.

Rare Exports: A Christmas Tale combines the visual sensibilities of films like Delicatessen, the affection for Christmas from Joe Dante’s films, and John Carpenter’s The Thing with a deconstruction of Santa Claus as an object of terror. Here, Santa Claus is a monster imprisoned in a mountain straight out of Lovecraft, a creature closer to Krampus than the jolly fat man from Miracle on 34th Street, a monster that steals your body and your identity to reproduce. This Santa Claus would probably run your grandmother with a sleigh drawn by reindeer, only he’s more interested in eating reindeer and kidnapping children than assaulting senior citizens.

For an 80-minute film, Rare Exports takes too long to set up and show the horror of Santa’s release, and the film doesn’t hit its central horror, action, or comedy beats as hard as he could have. My impatience with the film might also come from the tired father-son drama at the center of the film, or the fact that deconstructing Santa as a monster or deconstructing Christmas by injecting monsters into the holiday doesn’t feel original. It’s visually rich, but writer/director Jalmari Helander just doesn’t exploit the film’s ideas to their fullest, darkest potential.

For example, the film establishes that Santa reproduces by creating clones of itself as its helpers, but none of the main or supporting adult men in the story are lost to the process, which would have further cemented the father-son theme. The protagonists eventually reprogram the helpers into becoming Santa Clauses for department stores, which has implications of slavery (they’ve literally turned people into commodities to be rented or sold), but the film doesn’t acknowledge it. We’re left to cheer for how they’ve been able to save themselves from destitution after Santa killed all of the reindeer that they were going to slaughter for meat. The film tries to wink at us darkly, but I wish the film had bared its teeth more.

2. October 2 - Shadow of the Vampire (DVR) - Worth watching

3. October 3 - The Exorcism of Emily Rose (DVR) - Worth Watching

4. October 4 - Would You Rather (DVR) - Worth watching

5. October 5 - Excision (DVR) - Worth watching

6. October 6 - Evil Dead (2013) (DVR) - Meh

7. October 7 - Angel Heart (DVR) - Worth watching

8. October 8 - The Lords of Salem (DVR) - Meh

9. Near Dark *(1987) (DVR)

At this point, Near Dark has reached nearly legendary status among my circle of friends, so I started the film with great expectations and some trepidation after Angel Heart failed to meet expectations. Its mix of the sensibilities of the western, the biker movie, and the vampire movie is enticing, but what surprised me was how tender the film was. Mae probably loves Caleb more when he admits that he can’t be the kind of killer who can stand in Jesse’s clan of vampires alongside violent creatures like Severen or Homer. Mae turns Caleb because she’s lonely and wants someone with whom she could spend eternity; Jesse and Diamondback look back on his attack that turned her wistfully. It made me wonder what happens after the end of the film, when Mae has been turned back to human and can live with Caleb not to the end of time, but at least for a little while. We can’t be sure she’s from contemporary times, but it doesn’t look like she has trouble living in the modern world. But people grow and change; would Mae feel like she owes Caleb for turning her back to human? Would she resent Caleb? Would Caleb resent Mae for resenting him? Would the freedom from the existential loneliness of a vampire's existence be enough for Mae?

We never see the vampires bare their fangs, which is an interesting choice that recalls George Romero’s Martin. This choice positions them more like an outlaw biker gang or the Manson Family, a group of killers united by a charismatic leader. They’re forced to be scavengers by what they are; they could choose to withdraw from the world and emerge only when they need to feed, but since they’re uninhibited by society’s rules, they may as well enjoy what they have.

There’s probably something significant to the fact that Caleb and his sister, Sarah, are cared for by their single father, but I can’t figure out what it is. In westerns, the civilized woman, usually a mother, represents civilization that inspires the gunfighters. In this case, does the absence of a mother make Caleb and his sister vulnerable to Jesse and his gang of outsiders?

Near Dark, like its 1987 compatriot Angel Heart, was a surprisingly influential film. While the rule about vampires' fear of sunlight is critical to the vampire's story, Near Dark was the first to show in such graphic terms how sunlight affects vampires. Writer and director Kathryn Bigelow and writer Eric Red inject the specificity of a vampire's existence to standard action sequences like car chases (every window must be covered) and shoot-outs (the bullets can be laughed off, but the pinpricks of sunlight created by the bullet holes are dangerous). And you can draw a fairly straight line from Mae, her conscience, and her desire to be human to Angel of Buffy the Vampire Slayer and from Severen to Spike in Buffy, among other cool vampires. However, the Bigelow's style is derivative of James Cameron's The Terminator, which left a long shadow over action films of the 1980s, and the film looks very similar to Eric Red's The Hitcher.

The fairly happy ending that saw the use of barnyard blood transfusions to transform Caleb and Mae back human seemed weak, particularly when Adrian Pasdar's Caleb is the least interesting character of the film. Every moment we spend with Caleb and Mae is a moment we don't spend with Jesse, Diamondback, Severen, and Homer.

Finally, it bugged me that the soundtrack with its clangs and clashes sounded so familiar until I realized that Christopher Franke, who provided the soundtrack to Babylon 5, was a member of Tangerine Dream, which provided the soundtrack to Near Dark. There are moments when the soundtrack sounds exactly like the theme for Babylon 5’s third season opening credits.

10. Warm Bodies (2013) (DVR)

This movie was better than it had any right to be. Sure, it’s clichéd as hell; it even features a character named Julie and a balcony scene straight from Romeo and Juliet. Sure, John Malkovich is slumming it in this movie for the paycheck so obviously that it’s borderline offensive. And sure, the movie loses pretty much all momentum about halfway through the film, when the focus shifts on the unlikely romance between a zombie boy named “R,” played by Nicholas Hoult, and the aforementioned Julie, played by Teresa Palmer. But the opening act, particularly where R’s wry mental monologue takes us through his world, actually works very well.

The romance at the center of the film is problematic, to say the least. At best, it’s a story about a girl who falls in love with her undead kidnapper who might only be in love with her because he ate her boyfriend’s brain and inherited his memories and emotional connections. At worst, it brings up memories of abusive relationships like the one at the center of The CW’s Beauty and the Beast. Putting this aside, it’s still a fairly twee (they bond over vinyl records, which R prefers because the sound is more vibrant, or, you know, alive, and a carefully displayed bottle of Corona), low-key, passive teen romance. Whatever danger that existed at the heart of the romance between what is ostensibly a predator and its prey is neutered, and the external danger that comes from Julie’s father is thrown out because he basically steps back and accepts this weird, new relationship.

The world is a mishmash of concepts. On the one hand, we are invited to accept that the world is truly screwed. Beautiful teenagers and young adults have to be sent into the dangerous world beyond the city’s walls to scavenge for supplies. One of the manufacturing centers that the city relies on is overrun by zombies. The city, as far as it knows, is completely alone. On the other hand, detecting the zombie infection is as simple as a retinal scan, and those teenagers and young adults are treated to a video message by Malkovich’s character before they are sent outside.

Assimilation comes easy in this world. A bit of make-up, and a zombie can pass for a human. A bit of lurching and groaning, and a human can pass for a zombie. And with enough time, zombies can become humans again, and apparently people are more than happy to be romanced by former zombies, as the last scene featuring Rob Cordrry’s “M” shows. It’s the most optimistic view of human nature and its prejudices I've seen in a zombie film.

11. Byzantium (2013) (DVR)

The combination of Neil Jordan and Saorise Ronan sold me, and the lush and moody cinematography kept me. Jordan revisits the vampire’s ennui without reminding the viewer too much of his Interview With the Vampire, though both films feature vampires recounting their lives to nearby mortals. There are scenes where Ronan’s Eleanor, a vampire, is dressed in a red hood, that invite the viewers to remember the red hooded killer from Don’t Look Now and Little Red (and the Wolf). Unfortunately, what we see in flashbacks don’t reward the viewer for the time invested, and the time in the present seems very still.

The film tries to draw parallels about predatory violence between a man forcing a girl into a life of prostitution with a man turning a girl into a vampire, but we don’t spend enough time in the flashbacks to make those parallels stick. Jordan prefers the reserved tone, but the film feels practically lifeless for how much it holds back, especially in comparison to films like Let the Right One In or even Let Me In. Even the visceral moments of Byzantium feel like they were included only to wake the audience up every now and then; they feel intrusive.

12. Rare Exports: A Christmas Tale (2010) (DVR)

Any sufficiently clever child will remind you that “Santa” is an anagram for “Satan.” It’s not difficult to find the trace sinister elements that remain after years of pop culture telling us how about cuddly and comfortable we should feel about a character who uses slave labor in his workshop, who utilizes a global privacy-destroying surveillance system to monitor our behavior, who judges us by his code of morality, who breaks into our homes annually, and whose very code of behavior implies a threat if we violate his rules. The line between Santa Claus and the Punisher is fairly thin. Children can sense the Santa menace, which is why they hate to take photos with Santa cosplayers.

Santa Claus is a fairly popular character to deconstruct; Futurama’s Robot Santa Claus makes his implicit threat to everyone’s safety literal, while American Dad’s Santa Claus is a violent, vengeful baron of the North Pole. But even the more innocent deconstructions are vicious. Tim Allen’s character in The Santa Clause becomes Santa Claus against his will because he was infected by the Santa Clause, transmitting through donning the traditional Santa Claus outfit. His character undergoes a traumatic physical transformation, and his elfish paramilitary task force, the Effective Liberating Flight Squad, is deployed to break Santa Claus out of prison when he is captured by American authorities. In the end, Tim Allen’s character must abandon his family and his old life because he has been fully subsumed into the Santa Claus identity. No one would think that a Disney movie about Santa Claus would have so much body and psychological horror inside, but that’s the menace that Santa Claus presents leaking through the Disneyfied exterior.

Rare Exports: A Christmas Tale combines the visual sensibilities of films like Delicatessen, the affection for Christmas from Joe Dante’s films, and John Carpenter’s The Thing with a deconstruction of Santa Claus as an object of terror. Here, Santa Claus is a monster imprisoned in a mountain straight out of Lovecraft, a creature closer to Krampus than the jolly fat man from Miracle on 34th Street, a monster that steals your body and your identity to reproduce. This Santa Claus would probably run your grandmother with a sleigh drawn by reindeer, only he’s more interested in eating reindeer and kidnapping children than assaulting senior citizens.

For an 80-minute film, Rare Exports takes too long to set up and show the horror of Santa’s release, and the film doesn’t hit its central horror, action, or comedy beats as hard as he could have. My impatience with the film might also come from the tired father-son drama at the center of the film, or the fact that deconstructing Santa as a monster or deconstructing Christmas by injecting monsters into the holiday doesn’t feel original. It’s visually rich, but writer/director Jalmari Helander just doesn’t exploit the film’s ideas to their fullest, darkest potential.

For example, the film establishes that Santa reproduces by creating clones of itself as its helpers, but none of the main or supporting adult men in the story are lost to the process, which would have further cemented the father-son theme. The protagonists eventually reprogram the helpers into becoming Santa Clauses for department stores, which has implications of slavery (they’ve literally turned people into commodities to be rented or sold), but the film doesn’t acknowledge it. We’re left to cheer for how they’ve been able to save themselves from destitution after Santa killed all of the reindeer that they were going to slaughter for meat. The film tries to wink at us darkly, but I wish the film had bared its teeth more.

avengers23

Banned

1. October 1 - Sinister (DVR) - Worth watching

2. October 2 - Shadow of the Vampire (DVR) - Worth watching

3. October 3 - The Exorcism of Emily Rose (DVR) - Worth Watching

4. October 4 - Would You Rather (DVR) - Worth watching

5. October 5 - Excision (DVR) - Worth watching

6. October 6 - Evil Dead (2013) (DVR) - Meh

7. October 7 - Angel Heart (DVR) - Worth watching

8. October 8 - The Lords of Salem (DVR) - Meh

9. October 9 - Near Dark (DVR) - Worth watching

10. October 10 - Warm Bodies (DVR) - Worth watching

11. October 11 - Byzantium (DVR) - Meh

12. October 12 - Rare Exports: A Christmas Tale (DVR) - Meh

13. Eraserhead (1977) (DVR)

Ive loved James Camerons Aliens from the first time I saw it. It was scary (but not too scary for my prepubescent self). It had action. It had immensely quotable dialogue. Time passed, and at the bare minimum Id get at least the joy of watching a good film whenever I find it showing randomly on a cable television channel.

The image that impressed itself onto my young brain was the Alien Queens assault on Bishop on the Sulaco. The tail run through his chest, the milk white blood pouring from his mouth, the Queen tearing Bishop in two with its claws: that part of that scene stayed with me from the start. When I was younger, the more visceral horror of Aliens was particularly effective. As Ive gotten older, its the conceptual horror of the Xenomorph, in particular the invasive body horror that targets our unconscious fears about our own reproductive processes, that haunts me. In parenthood, theres no one to hear you scream.

Even if Jack Nance, the protagonist of David Lynchs Eraserhead, wanted to scream out his anger, fear, frustration, confusion, Im not sure anyone would be able to hear him over the pervasive sound, the industrial groaning and nervous background white noise that seeps from every corner of his world. The hissing, crashing, and groaning should be a sign, much like a babys cry, that something is wrong. But Nance cant figure it; hes barely motivated enough to take care of his baby, much less solve the worlds problems.

As critics and David Lynch historians have discussed, Eraserhead explored Lynchs own fears about becoming a parent, specifically a parent of a child who was born with special needs. Eraserhead brought back the sense of panic about figuring out what this screaming bag of meat that left the womb biologically nine months too early wants even though its incapable of communicating its needs, much less its desires, the frustration born from sleep deprivation, the irrational anger at the partner who can be so easily blamed for bringing the troubles of parenthood to your life, and the confusion about the choice to be bound sexually and emotionally to another person for the rest of your life when other sexual partners look so inviting and free of trouble.

Lynchs ambivalence about the United States and escapism that are embedded in his later works have their foundation in Eraserhead as well, and you can see the beginnings of images from his later works here. The Velvet room and the opera scene from Mulholland Drive can trace their lineage to the Woman in the Radiators performance in Eraserhead. Mary X is the first of Lynchs blondes. Nance tries to find escape from the world with his neighbor, the Beautiful Girl Across the Hall, and by watching the Lady in the Radiators performance while lying on his bed in his one bedroom apartment, much like Diane tried to escape the ugly truth in fantasy in Mulholland Drive, but the only way he can find peace is by murdering his child, which brings an end to his world.

Id argue that this is Lynchs masterpiece, a masterfully crafted and profoundly personal film. Lynchs surrealist tendencies hadnt overwhelmed his storytelling yet, and it has a passion that his other films, other than The Straight Story, lack.

14. Dark Skies (2013) (DVR)

Last year, I watched Fire in the Sky as a part of the marathon, and it made a great alien abduction panic combo with the Slumber Party Alien Abduction segment of V/H/S 2. After watching Dark Skies, I wish that I had stuck to the original plan to watch Alien Abduction: Incident in Lake County instead. Dark Skies is a serviceable alien abduction horror film, but it lacks any remarkably scary moments. It felt tame, and it felt like a wasted opportunity.

I appreciate that Dark Skies plays closer to a supernatural ghost haunting film, using some of the same faerie tricks (taking food from the refrigerator, stacking things in the kitchen, mysteriously triggered perimeter alarms, distortion of electronic surveillance equipment) that films like Paranormal Activity used to build the tension and show that things are amiss in the household of Daniel (Josh Hamilton) and Lacy (Keri Russell) Barrett, than an alien abduction film like Fire in the Sky. It borrowed a scare from The Birds. It even featured Daniel examining the surveillance footage frame by frame in order to find the invaders of his home, much like the protagonist in Paranormal Activity. The film felt like it had very little new to say.

It also features a huge info dump from J.K. Simmons conspiracy theorist/alien abductee about 2/3 of the way through the film in order to set up the final siege scene. Then, the director decides to skip showing most of that siege scene, which seemed like a curious decision. The film had built to this confrontation between the family and the invaders. Instead, the film switches focus from the Daniel and Lacy to their sons to try to arrive at an emotional conclusion that seemed wrong for the film that director/writer Scott Stewart had created.

Throughout the film, Daniels unemployment creates tension with Lacy, which then seeps into his interactions with his sons and neighbors. Hes clearly ashamed by his inability to find a job. This had great emotional potential, and Keri Russell plays Lacys frustration about Daniel lying to her about getting a job and her joy when Daniel actually does get a job in an overall strong, committed performance. Similarly, Simmons makes the most of his limited role as an exposition machine. But the films conclusion hinges on a deep feeling of estrangement between Daniel and his eldest son, Jesse, that isnt explained by the inciting incident of their relationships rupture that we see in the film.

Besides providing an exposition dump, Simmonss character also blatantly spells out Stewarts theme of family unity in the face of hard times to Daniel and the audience. I can see how Stewart tried to use the alien abduction and home invasion as the crucible by which the family can gain strength, but the film then puts that idea down with Simmonss fatigue and fatalism and its own ending. The family put aside its differences, which werent very well explored, to come together against the unknowable threat from the outside. The ultimately fail to keep the family together against that threat, which seemed an unearned twist.

The more I think about Dark Skies, the more I feel a sense of regret about how it wasted its potential.

15. The Purge (2013) (DVR)

The Purge writes a check for suspension of disbelief that it cant cash. It takes cinematic shortcuts to posit the idea that humans are naturally aggressive, almost as though were tainted with an Original Sin, and that we must purge ourselves of this sin by acting out against our fellow man. The film tries to detach crime from poverty, from mental illness, from desperation born from chemical addiction, which is nonsense. It points to the characters who suppressed their animalistic urges to hurt and kill as survivors worthy of admiration to give the film a sense of moral grounding, but it doesnt actually make a case for why their morality is superior to the masked killers who hunt the homeless on Purge Night for thrills or their neighbors who want to kill the protagonists out of jealousy. It leaves us to project our morality onto the characters and their actions, which feels like an incomplete dialogue.

The world is drawn in just enough to inspire questions. How does the government treat citizens like the Sandin family who barricade themselves against the outside world and refuse to participate in Purge Night? The government clearly believes in the cathartic (or economic) effects of Purge Night, but the movie effectively divides American citizens between those who kill and those who wont. Do the people who refrain from killing (or committing other crimes) on Purge Night judge those who participated during the rest of the year? Do those who kill judge those who refrained and find them to be disloyal or weak? Killing is the shortcut, but the film makes a point that all crime is legal on Purge Night. One can assume that rapes are committed on Purge Night. What happens to children conceived from rape? If a citizen fires a bullet at one second before Purge Night ends and the bullet hits the intended victim after Purge Night has ended, is the shooter charged with a crime? How do religious authorities, particularly the Christian denominations, reconcile the governments directive of Purge Night with their doctrines and prohibitions against killing? The writer chose to set the film in the United States in a specific time (2022), which opens the film to scrutiny. Unfortunately, the dystopia the movie presents doesnt stand up to examination.

Jason Blum, The Purges producer, claimed that his production company is in the business of making scary movies, not political movies. But if theres a political message baked into [the film], I wont turn it down. Despite his claim, The Purge is inherently a political film, from its premise to the flavor sprinkled throughout the film to provide context. Talk radio commentators wonder whether Purge Night is secretly designed to exterminate all non-contributing members of society. They discuss how the real victims are the poor who cant afford to protect themselves. The leader of the gang that laid siege on the Sandins home refers to his partners as the haves and their intended homeless victim as filthy swine and social parasite. They claim their right to kill based on what they think of as inherent superiority by din of their higher economic standing.

And we havent even touched on the fact that film positions these white, rich, young masked killers to be hunters of a black homeless man.

Politics and racial dynamics aside, the films creators tell their tale clumsily. The filmmakers mistake taking shortcuts for brevity. Were not given sufficient time or context to gain a sense of James Sandin, played by Ethan Hawke, or Jamess son, Charlie, played by Max Burkholder. When Charlie deactivates the security system to let the unnamed homeless stranger into his home, its unclear why other than the fact that the plot necessitated it. The story of Jamess daughters boyfriend, who tries to assert his right to date the Sandin girl, Zoey, played by Adelaide Kane, above her fathers objections by pointing a gun at him on Purge Night goes nowhere; Zoey doesnt seem particularly traumatized by the fact that her father killed her boyfriend. The unnamed homeless stranger who is provided refuge in the Sandins home goes missing for most of the film; were given no reason to root for his survival at the cost of the Sandins safety other than the biases that we bring to the film. When James decides to fight, his wife, Mary, played by Lena Headey, is not asked for her opinion even though shell have to take up arms against the masked killers who will invade their home. In fact, Mary could probably be extracted from the film altogether without dramatically changing the film; its a waste of Headey, who plays steely women so well. Furthermore, the film doesnt explore Jamess motivation to fight. He says to Mary that they have to fight to protect their home. But did he choose because he believed in the castle doctrine, or did he choose because he couldnt bring himself to give the unnamed homeless stranger, bound and subdued by the Sandins at this point, to the mob? Its a clumsy take on material explored by Peckinpah in Straw Dogs.

The handheld cameras shakiness obscures our view of almost everything, which brings us to the inherent contradiction of the film. No one can deny that The Purge is a genre film, slotted somewhere between Assault on Precinct 13 and Straw Dogs. The viewers are invited to root for the Sandins as they kill the masked invaders in spectacularly violent ways. Yet the film ends by asserting that the best thing for people is to repress their irrepressible violent tendencies, though releasing those tendencies has apparently brought the country safety and economic prosperity. So why should we repress those tendencies other than a sense of goodness, which means little when the film also asserts that people are inherently violent?

The Purge frustrated me. A tweak of the premise, perhaps by choosing not to set the film in the United States in the near future, could at least dampen questions about its world-building. The premise is still interesting; its the idea of boisterous celebration, overturning social conventions, and debauchery before periods of penance and confession writ large. As a film of plot and character motivations, it feels half-baked, and it relies on the audiences own biases and opinions to make itself work, rather than holding a conversation with the audience as Funny Games, for example, does.

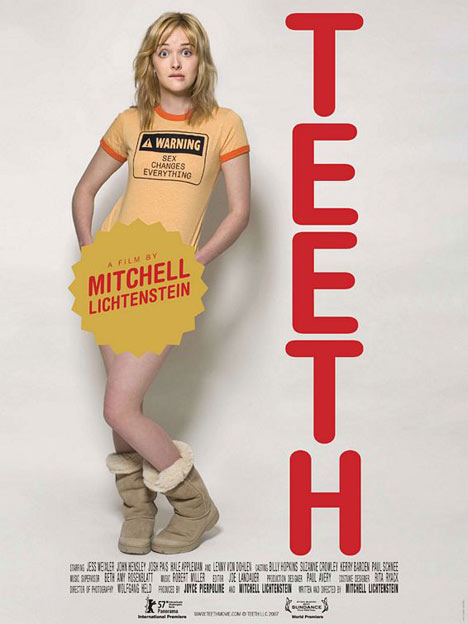

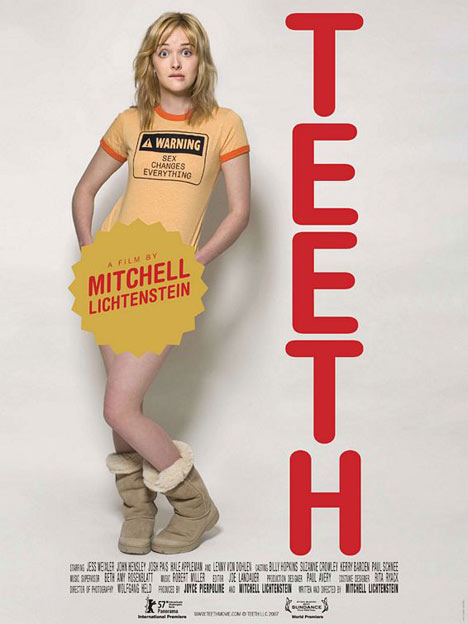

16. Teeth (2007) (DVR)

I thought this was cleverly tongue-in-cheek, horrifying, and wince-inducing at the same time. The movie begins with a pair of atomic power plant silos rising above the town like a great, heaving, life-creating and life-destroying bosom. The camera then tilts down to see an all-American nuclear family, only its a blended family. The idea of the nuclear family and the specter of nuclear power haunt this film; every so often, the film reminds us of radiations power to mutate, which ties into the general teenage anxiety about the changes to our bodies and ourselves.

Nuclear power is tied to the town and to the family of Bill, his son Brad, Kim, and her daughter Dawn. Kims developed cancer, and no one in the film explicitly blames the nuclear plant. But the film makes the judgment for us by reminding us periodically of the plants presence.

Pheromones, like radiation, cant be detected by our naked senses; the town is equally covered by both. Dawn is committed to maintaining her purity, which she defines by chastity, in the face of hormone driven temptation. She characterizes her virginity as the most precious gift of all, but she discovers that its a target; the Promise Ring she wears just marks her as a prize or the subject of a bet.

Dawn eventually realizes the powers of her developing body despite the towns male hierarchys best attempts to keep her and everyone else in the dark about something as fundamental as female reproductive anatomy. The schools textbooks cover anatomical drawings of the vagina with a gold sticker; the biology teacher stumbles over even saying the words vagina or vulva and expresses approval of the towns initiative to keep its teenagers pure by withholding knowledge from them; Dawns first gynecologist is a man, who exploits his profession by sexually assaulting women.

Writer-director Mitchell Lichtenstein straddles the line between horror and satire skillfully, shifting and pivoting from one sensibility to the other and getting the balance mostly just right. It depicts the men who try to take advantage of Dawn as getting what they deserve; the films Carrie mixed with Reefer Madness with a touch of I Spit on Your Grave. Its probably the smartest horror film next to Eraserhead Ive seen so far this year.

2. October 2 - Shadow of the Vampire (DVR) - Worth watching

3. October 3 - The Exorcism of Emily Rose (DVR) - Worth Watching

4. October 4 - Would You Rather (DVR) - Worth watching

5. October 5 - Excision (DVR) - Worth watching

6. October 6 - Evil Dead (2013) (DVR) - Meh

7. October 7 - Angel Heart (DVR) - Worth watching

8. October 8 - The Lords of Salem (DVR) - Meh

9. October 9 - Near Dark (DVR) - Worth watching

10. October 10 - Warm Bodies (DVR) - Worth watching

11. October 11 - Byzantium (DVR) - Meh

12. October 12 - Rare Exports: A Christmas Tale (DVR) - Meh

13. Eraserhead (1977) (DVR)

Ive loved James Camerons Aliens from the first time I saw it. It was scary (but not too scary for my prepubescent self). It had action. It had immensely quotable dialogue. Time passed, and at the bare minimum Id get at least the joy of watching a good film whenever I find it showing randomly on a cable television channel.

The image that impressed itself onto my young brain was the Alien Queens assault on Bishop on the Sulaco. The tail run through his chest, the milk white blood pouring from his mouth, the Queen tearing Bishop in two with its claws: that part of that scene stayed with me from the start. When I was younger, the more visceral horror of Aliens was particularly effective. As Ive gotten older, its the conceptual horror of the Xenomorph, in particular the invasive body horror that targets our unconscious fears about our own reproductive processes, that haunts me. In parenthood, theres no one to hear you scream.

Even if Jack Nance, the protagonist of David Lynchs Eraserhead, wanted to scream out his anger, fear, frustration, confusion, Im not sure anyone would be able to hear him over the pervasive sound, the industrial groaning and nervous background white noise that seeps from every corner of his world. The hissing, crashing, and groaning should be a sign, much like a babys cry, that something is wrong. But Nance cant figure it; hes barely motivated enough to take care of his baby, much less solve the worlds problems.

As critics and David Lynch historians have discussed, Eraserhead explored Lynchs own fears about becoming a parent, specifically a parent of a child who was born with special needs. Eraserhead brought back the sense of panic about figuring out what this screaming bag of meat that left the womb biologically nine months too early wants even though its incapable of communicating its needs, much less its desires, the frustration born from sleep deprivation, the irrational anger at the partner who can be so easily blamed for bringing the troubles of parenthood to your life, and the confusion about the choice to be bound sexually and emotionally to another person for the rest of your life when other sexual partners look so inviting and free of trouble.

Lynchs ambivalence about the United States and escapism that are embedded in his later works have their foundation in Eraserhead as well, and you can see the beginnings of images from his later works here. The Velvet room and the opera scene from Mulholland Drive can trace their lineage to the Woman in the Radiators performance in Eraserhead. Mary X is the first of Lynchs blondes. Nance tries to find escape from the world with his neighbor, the Beautiful Girl Across the Hall, and by watching the Lady in the Radiators performance while lying on his bed in his one bedroom apartment, much like Diane tried to escape the ugly truth in fantasy in Mulholland Drive, but the only way he can find peace is by murdering his child, which brings an end to his world.

Id argue that this is Lynchs masterpiece, a masterfully crafted and profoundly personal film. Lynchs surrealist tendencies hadnt overwhelmed his storytelling yet, and it has a passion that his other films, other than The Straight Story, lack.

14. Dark Skies (2013) (DVR)

Last year, I watched Fire in the Sky as a part of the marathon, and it made a great alien abduction panic combo with the Slumber Party Alien Abduction segment of V/H/S 2. After watching Dark Skies, I wish that I had stuck to the original plan to watch Alien Abduction: Incident in Lake County instead. Dark Skies is a serviceable alien abduction horror film, but it lacks any remarkably scary moments. It felt tame, and it felt like a wasted opportunity.

I appreciate that Dark Skies plays closer to a supernatural ghost haunting film, using some of the same faerie tricks (taking food from the refrigerator, stacking things in the kitchen, mysteriously triggered perimeter alarms, distortion of electronic surveillance equipment) that films like Paranormal Activity used to build the tension and show that things are amiss in the household of Daniel (Josh Hamilton) and Lacy (Keri Russell) Barrett, than an alien abduction film like Fire in the Sky. It borrowed a scare from The Birds. It even featured Daniel examining the surveillance footage frame by frame in order to find the invaders of his home, much like the protagonist in Paranormal Activity. The film felt like it had very little new to say.

It also features a huge info dump from J.K. Simmons conspiracy theorist/alien abductee about 2/3 of the way through the film in order to set up the final siege scene. Then, the director decides to skip showing most of that siege scene, which seemed like a curious decision. The film had built to this confrontation between the family and the invaders. Instead, the film switches focus from the Daniel and Lacy to their sons to try to arrive at an emotional conclusion that seemed wrong for the film that director/writer Scott Stewart had created.

Throughout the film, Daniels unemployment creates tension with Lacy, which then seeps into his interactions with his sons and neighbors. Hes clearly ashamed by his inability to find a job. This had great emotional potential, and Keri Russell plays Lacys frustration about Daniel lying to her about getting a job and her joy when Daniel actually does get a job in an overall strong, committed performance. Similarly, Simmons makes the most of his limited role as an exposition machine. But the films conclusion hinges on a deep feeling of estrangement between Daniel and his eldest son, Jesse, that isnt explained by the inciting incident of their relationships rupture that we see in the film.

Besides providing an exposition dump, Simmonss character also blatantly spells out Stewarts theme of family unity in the face of hard times to Daniel and the audience. I can see how Stewart tried to use the alien abduction and home invasion as the crucible by which the family can gain strength, but the film then puts that idea down with Simmonss fatigue and fatalism and its own ending. The family put aside its differences, which werent very well explored, to come together against the unknowable threat from the outside. The ultimately fail to keep the family together against that threat, which seemed an unearned twist.

The more I think about Dark Skies, the more I feel a sense of regret about how it wasted its potential.

15. The Purge (2013) (DVR)

The Purge writes a check for suspension of disbelief that it cant cash. It takes cinematic shortcuts to posit the idea that humans are naturally aggressive, almost as though were tainted with an Original Sin, and that we must purge ourselves of this sin by acting out against our fellow man. The film tries to detach crime from poverty, from mental illness, from desperation born from chemical addiction, which is nonsense. It points to the characters who suppressed their animalistic urges to hurt and kill as survivors worthy of admiration to give the film a sense of moral grounding, but it doesnt actually make a case for why their morality is superior to the masked killers who hunt the homeless on Purge Night for thrills or their neighbors who want to kill the protagonists out of jealousy. It leaves us to project our morality onto the characters and their actions, which feels like an incomplete dialogue.

The world is drawn in just enough to inspire questions. How does the government treat citizens like the Sandin family who barricade themselves against the outside world and refuse to participate in Purge Night? The government clearly believes in the cathartic (or economic) effects of Purge Night, but the movie effectively divides American citizens between those who kill and those who wont. Do the people who refrain from killing (or committing other crimes) on Purge Night judge those who participated during the rest of the year? Do those who kill judge those who refrained and find them to be disloyal or weak? Killing is the shortcut, but the film makes a point that all crime is legal on Purge Night. One can assume that rapes are committed on Purge Night. What happens to children conceived from rape? If a citizen fires a bullet at one second before Purge Night ends and the bullet hits the intended victim after Purge Night has ended, is the shooter charged with a crime? How do religious authorities, particularly the Christian denominations, reconcile the governments directive of Purge Night with their doctrines and prohibitions against killing? The writer chose to set the film in the United States in a specific time (2022), which opens the film to scrutiny. Unfortunately, the dystopia the movie presents doesnt stand up to examination.

Jason Blum, The Purges producer, claimed that his production company is in the business of making scary movies, not political movies. But if theres a political message baked into [the film], I wont turn it down. Despite his claim, The Purge is inherently a political film, from its premise to the flavor sprinkled throughout the film to provide context. Talk radio commentators wonder whether Purge Night is secretly designed to exterminate all non-contributing members of society. They discuss how the real victims are the poor who cant afford to protect themselves. The leader of the gang that laid siege on the Sandins home refers to his partners as the haves and their intended homeless victim as filthy swine and social parasite. They claim their right to kill based on what they think of as inherent superiority by din of their higher economic standing.

And we havent even touched on the fact that film positions these white, rich, young masked killers to be hunters of a black homeless man.

Politics and racial dynamics aside, the films creators tell their tale clumsily. The filmmakers mistake taking shortcuts for brevity. Were not given sufficient time or context to gain a sense of James Sandin, played by Ethan Hawke, or Jamess son, Charlie, played by Max Burkholder. When Charlie deactivates the security system to let the unnamed homeless stranger into his home, its unclear why other than the fact that the plot necessitated it. The story of Jamess daughters boyfriend, who tries to assert his right to date the Sandin girl, Zoey, played by Adelaide Kane, above her fathers objections by pointing a gun at him on Purge Night goes nowhere; Zoey doesnt seem particularly traumatized by the fact that her father killed her boyfriend. The unnamed homeless stranger who is provided refuge in the Sandins home goes missing for most of the film; were given no reason to root for his survival at the cost of the Sandins safety other than the biases that we bring to the film. When James decides to fight, his wife, Mary, played by Lena Headey, is not asked for her opinion even though shell have to take up arms against the masked killers who will invade their home. In fact, Mary could probably be extracted from the film altogether without dramatically changing the film; its a waste of Headey, who plays steely women so well. Furthermore, the film doesnt explore Jamess motivation to fight. He says to Mary that they have to fight to protect their home. But did he choose because he believed in the castle doctrine, or did he choose because he couldnt bring himself to give the unnamed homeless stranger, bound and subdued by the Sandins at this point, to the mob? Its a clumsy take on material explored by Peckinpah in Straw Dogs.

The handheld cameras shakiness obscures our view of almost everything, which brings us to the inherent contradiction of the film. No one can deny that The Purge is a genre film, slotted somewhere between Assault on Precinct 13 and Straw Dogs. The viewers are invited to root for the Sandins as they kill the masked invaders in spectacularly violent ways. Yet the film ends by asserting that the best thing for people is to repress their irrepressible violent tendencies, though releasing those tendencies has apparently brought the country safety and economic prosperity. So why should we repress those tendencies other than a sense of goodness, which means little when the film also asserts that people are inherently violent?

The Purge frustrated me. A tweak of the premise, perhaps by choosing not to set the film in the United States in the near future, could at least dampen questions about its world-building. The premise is still interesting; its the idea of boisterous celebration, overturning social conventions, and debauchery before periods of penance and confession writ large. As a film of plot and character motivations, it feels half-baked, and it relies on the audiences own biases and opinions to make itself work, rather than holding a conversation with the audience as Funny Games, for example, does.

16. Teeth (2007) (DVR)

I thought this was cleverly tongue-in-cheek, horrifying, and wince-inducing at the same time. The movie begins with a pair of atomic power plant silos rising above the town like a great, heaving, life-creating and life-destroying bosom. The camera then tilts down to see an all-American nuclear family, only its a blended family. The idea of the nuclear family and the specter of nuclear power haunt this film; every so often, the film reminds us of radiations power to mutate, which ties into the general teenage anxiety about the changes to our bodies and ourselves.

Nuclear power is tied to the town and to the family of Bill, his son Brad, Kim, and her daughter Dawn. Kims developed cancer, and no one in the film explicitly blames the nuclear plant. But the film makes the judgment for us by reminding us periodically of the plants presence.

Pheromones, like radiation, cant be detected by our naked senses; the town is equally covered by both. Dawn is committed to maintaining her purity, which she defines by chastity, in the face of hormone driven temptation. She characterizes her virginity as the most precious gift of all, but she discovers that its a target; the Promise Ring she wears just marks her as a prize or the subject of a bet.

Dawn eventually realizes the powers of her developing body despite the towns male hierarchys best attempts to keep her and everyone else in the dark about something as fundamental as female reproductive anatomy. The schools textbooks cover anatomical drawings of the vagina with a gold sticker; the biology teacher stumbles over even saying the words vagina or vulva and expresses approval of the towns initiative to keep its teenagers pure by withholding knowledge from them; Dawns first gynecologist is a man, who exploits his profession by sexually assaulting women.

Writer-director Mitchell Lichtenstein straddles the line between horror and satire skillfully, shifting and pivoting from one sensibility to the other and getting the balance mostly just right. It depicts the men who try to take advantage of Dawn as getting what they deserve; the films Carrie mixed with Reefer Madness with a touch of I Spit on Your Grave. Its probably the smartest horror film next to Eraserhead Ive seen so far this year.